|

Walking down the rocky gravel path, the wind nipped at my numbing cheeks and nose. In this moment I thanked myself for neither wearing my hair up nor getting it cut any shorter. Pulling my hood up over my head and stuffing my belongings - binos, pencil pouch and sketchbook - into various pockets, I tugged my sleeves over my fingertips and crunched my hands into fists. the sound of each footstep on the gravel seemed obnoxiously loud compared to the overwhelming silence of the wood. Broken only by the sound of leaves rustling in the wind and the occasional far-off bird call, the silence, a seeming friend of the cold, accompanied me to the stream.

0 Comments

But ask the animals, and they will teach you, or the birds in the sky, and they will tell you; or speak to the earth, and it will teach you, or let the fish in the sea inform you. Which of all these does not know that the hand of the Lord has done this? In his hand is the life of every creature and the breath of all mankind. Job 12:7-10 This is by far my favorite passage in Scripture. It not only suggests an innate awareness of God in the essences of every living creature but also incentivizes us as believers to make a greater priority the issue of conservation. The church, at least in my experience, has not demonstrated much support as it pertains to the preservation of the natural world and to wildlife conservation (somebody PLEASE correct me if I'm wrong — it would be quite encouraging). For whatever reason that may be, my hope is that followers of Christ can grow to love and appreciate nature, especially in light of Job 12:7-10. Perhaps if we approached the issue with an understanding that we can learn things about God through nature we would cherish our earth more. So I beg the question: how can we know God better through the natural world? 1. Authors of the Bible often use elements of nature to depict and describe God.  Many attributes of God are described in Scripture using references to nature:

These examples are just a handful of the passages in Scripture that utilize our understanding of nature to help us understand God. There are plenty more examples. If you've ever heard the roaring of a violent wind or experienced the intimidating presence of a lion or seen the strength of deeply rooted trees, you have had a taste of what God is like. Nature sheds light on unfathomable traits of God. 2. Learning about the natural world helps us love God with all our minds. Jesus replied: “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’" Matthew 22:37 According to John Ortberg in his book Who Is This Man?, "To love God with your mind begins with being curious about God." He goes on to say, operating from the understanding that God created everything, "Therefore, anytime we learn something that's true, anytime we learned about how creation works or even about math or logic, we are actually thinking God's thoughts." He even suggests that the opposition to science is one of the most visible sins of the church. My jaw dropped when I read this. As someone who has been deeply passionate about animals and wildlife conservation since I was a kid, I have longed to see the convergence of science and faith in the church. Granted, I rarely do, and this was the first time that I felt someone had spoken out in this way about the church and its relationship with science. I was both amazed and comforted. To know that the pursuit of science — of understanding the world around us — can be seen as a method of discipleship was overjoying and encouraging to me. Learning how ecosystems function, discovering the intricacy of every interconnected biotic and abiotic factor in the world, understanding the behavior of animals in their proper contexts — all of these things help us love God with all our minds. The deeper we press in our relationship with God as individuals, the more He will reveal to us about Himself. And just like our universe, there is no end to what can be known and learned about God. 3. We come to know a creator by their creation. For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities — his eternal power and divine nature — have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse. Romans 1:20 Hey, Paul said it, not me. Here's the bottom line: nature is a reality by which we know everything around us, and there are invisible qualities of God that are clearly reflected in it. This idea makes logical sense: nature was created by God and thus is a way by which we can know and understand Him, His character and His thoughts. In what ways are His eternal power and divine nature revealed, though? I'll give you a few examples. In the same way that nature can be both relentlessly unforgiving and serenely enlivening can God be characterized by righteous wrath and unrelenting love. Or consider light, which is both a wave and a particle. This oxymoronic quality of God can be better understood by looking at nature, and that is only one of the things that we come to learn about God. As another example, take natural disasters like hurricanes, tsunamis, earthquakes, etc. They have oft been considered with negative connotations, which is understandable. They have very disastrous, real consequences that deeply affect people's lives. I have always been enamored by and drawn to them (I KNOW I'm not the only person who can say this). My friend pressed me to think about why I was so drawn to them, and this is what I concluded: they are pure power. Not arbitrary power that people are convinced they have because they hold "such and such" title. There is nothing we can do to stop natural disasters; we can only respond to their arrival with preparation. Take Hurricane Katrina, which hit New Orleans in August 2005, causing unimaginable damage along the Gulf Coast. There was nothing that could be done except prepare and respond. Natural disasters have the power to level cities and redefine our perception of normal. And yet even these are just a glimpse of the power of God: unstoppable, fierce, unpreventable, dangerous. 4. People encounter God in the wilderness. There are countless biblical accounts of people encountering God in the wilderness. Here are a few:

There are SO many more examples. This kind of encounter with God in the wilderness happens today, too. There are plenty of people who go into the wilderness and encounter God, either intentionally or unintentionally. In nature we experience a kind of freedom, an unattachment from the world by which we often find ourselves constrained. Through our relationships with Him, God wants us to be able to experience that same amount of freedom and liberation from the world, from fear, from unwarranted expectations and from so much else. The physical freedom we experience in nature is reminiscent of the spiritual freedom we encounter in the presence of God. As is evidenced throughout the Bible, nature and animals are things of importance to God. Rocks and mountains worship Him, animals trust Him to provide, the wind and the waves obey Him and the unending galaxy reflects His infinite essence. God utilizes that which He has created to help us know Him better, so I pray that we can grow in our appreciation and understanding of nature and wild animals.

I encourage you to take some time for personal reflection. Maybe take a walk or spend a few minutes outside. Look at the natural world around you: the bugs, the leaves, the flowers, the clouds, the birds. Ask the Lord to reveal Himself to you in a new way through nature or through animals. Please let me know what comes up — I'd love to hear about it. :) In honor of World Elephant Day today, I wanted to share about one of my most memorable elephant encounters in the Okavango Delta. Just before we sat down for lunch on August 3rd, I asked one of my trainers if I could accompany him and another to the watering hole — named Hidden Lagoon — to help fix the water pump that elephants had yet again uncovered. The Okavango Delta was experiencing its worst drought in decades, water had failed to reach our location yet, and Hidden Lagoon was the only place for miles that served as a dependable water source for all the surrounding animals. The water is pumped out of the ground using energy collected by a series of solar panels, pushed through pipes, and emptied into the watering hole to provide for water-dependent animals in the area. Those working at African Guide Academy tried time and time again to keep the pump and the well out of the grasp of thirsty elephants' trunks. Elephants are incredibly intelligent animals and were able to sense the water coming up from underground and going through the pipes into the watering hole. When they had consumed all the water, they went for the pump. The pump itself was covered in a cage that had been tied down with wires, some of which the elephants seemed to have snapped with their pure strength. Yet again, the elephants had exposed this pump to a point at which it had to be recovered or it would potentially be damaged. This is what we would try to remedy during the excursion. Later that afternoon Mike, Jono and I jumped into the vehicle and took off on our way to the watering hole. As we rounded a bend in the path and Hidden Lagoon came into sight in the distance, Mike and Jono both groaned upon seeing the great number of elephants that were mingling around the water. Mike counted 47 elephants and I later counted 54. They were everywhere — under every patch of shade and playing in every puddle of muddied water. One massive bull elephant was even getting a nice scratch between two trees. There were at least 5 separate breeding herds and countless bulls, and their ages ranged anywhere from one year to forty years. The quickly depleting water collection was completely surrounded by these gorgeous animals. Though it was winter and the sun was still far from its greatest strength, the midday temperatures pushed each elephant to desperation for a sip of water. As soon as we began our approach closer into the lagoon some of the elephants began clearing out. However, those who had been patiently waiting in the cool of the shade filled the empty space: we were completely engulfed in a sea of elephants. Parking between the watering hole and the pump, we were greeted by massive logs and leadwood branches strewn around, indicative of the elephants' handiwork. Mike, Jono and I were going to strategically replace the limbs in such a way that the elephants wouldn't be able to uncover the pump again. Jono shut off the vehicle and the three of us sat quietly, letting the elephants settle their nerves and grow their trust in us, though their wariness was outweighed by pure desperation for water. After about 10 minutes of waiting, strategizing and observing, Jono decided that the coast was clear. Though we were still surrounded on every possible side with elephants continuing to pour into the area, they were, at the moment, at a safe enough distance for us to begin our work Initially I sat on the edge of the vehicle, wanting to stay out of the way until instructed otherwise. I watched the way that all the different elephants interacted with each other and with us:

These different interactions occurred simultaneously, all in a matter of minutes. After a few logs were moved by Mike and Jono, I heard Mike say, "I'm sure Kerr and I can move this big one." Smiling from ear to ear, I leapt off the side of the vehicle, adrenaline coursing through my body: I was on the ground 15 meters away from several dozen elephants, trying to help preserve their water access. My heart was soaring — this was a once-in-a-lifetime experience and yet I wanted it to last forever. As soon as I joined the two on the ground, Jono went through an operating procedure with me: if an elephant came too close, I was to immediately get in the vehicle. If neither Jono nor Mike was able to get in, I was to immediately start the vehicle, which would startle the elephants enough to ward them off. When you are in that kind of situation, there can be no hesitation. You have to have an action plan established in case things go wrong. The three of us worked under the sun, strategically placing and intertwining massive limbs in hopes that the elephants would have a much harder time removing the logs if they were packed down a little better. When an elephant became too curious, Mike talked to the animal, which usually curbed its curiosity. We all laughed, bantered and worked in awe of the circumstance in which we found ourselves: surrounded by over 50 elephants on every side, moving massive logs that would take them one swish of the trunk to remove. Watching each other's backs, we kept an eye out for some of the more testy elephants. At one point, as Mike and I stood up from placing a massive log on the heaping pile, I heard a rustle and Jono say from behind me, "Uh, Kerrington, move to the vehicle and get in, but move slowly." I looked up and Mike nodded, confirming Jono's instruction as I gently set down the branch I was holding and side-stepped to the vehicle with my back towards whatever was happening in front of Jono. "Slowly, slowly…" Jono reassured. I felt excitement rather than fear, as I trusted Jono and Mike completely, knowing that hesitation or failure to heed their commands would end poorly in one way or another. After a few steps, Jono said, "Okay, quickly. Get in the vehicle quickly." Another three steps and I was in the relative safety of the vehicle, watching as Mike and Jono jumped in behind me. I looked to both Jono and Mike and was met by beaming faces, their intoxication with adrenaline just as evident as my own. An unseen elephant female — called a cow — had surprised Jono as she led her herd out of the brush towards water, coming too close for us to comfortably remain on foot. The matriarch approached the vehicle closer, trying to defend her calf and herd with a mock charge, flapping ears and trumpeting. Jono scrambled for the keys and flipped the ignition on. The growling motor startled the cow, and she soon realized not only that we weren't backing down but also that we weren't a threat. She slowly and very cautiously led her calf and herd around the vehicle to the water. At her closest, she was likely 10 meters away from us. The three of us sighed in relief, as we could now resume the nearly-completed task. "Kerrington," Jono ordered, "Stay in the vehicle and keep a watchful eye out for elephants who come too close." "Yeah, and if they do get too close, just start talking to them. They'll understand you," Mike added. As they jumped back onto the ground I returned to my perch on the edge of the vehicle, turning and trying to keep my eyes on every elephant that wandered too close. The nervous cow did approach closer, and I began talking to her, saying, "Hey now, it's okay. No need to worry about us." I spoke at a volume slightly louder than normal with inflection in my voice, similar to the way I would talk to my dogs. Jono and Mike placed the last log on the pile as an elephant approached, causing them to jump back into the vehicle. There was still one massive leadwood limb that needed to be added, but it was far too heavy for Jono and Mike to move alone. So there I sat once more, listening to Mike and Jono plan and strategize what the next move would be. Jono decided that when the nervous cow turned her back to us he would jump out and attach a tow rope to the limb so that we could very securely place it on the heap. Mike jumped into the driver's seat and I stabilized myself on the edge using the roof railing. As Jono guided Mike's driving from the back, the vehicle made its way towards Jono in reverse. The brief ride was bumpy and loud, enough to startle the elephants that were closest to us, giving Jono plenty of safe space to work. After Mike parked, Jono once again waited for things to settle before quietly slipping out to attach the tow rope. Sneaking around the corner of the vehicle, Jono was met with the questioning, watchful gaze of the cow. Mike laughed and said, "Dude, there's no way you're sneaking up on her." Jono shook his head laughing and attached the tow rope to the branch before stepping back by the vehicle once more. "Alright, drive," Jono told Mike. As he accelerated I felt the resistance of the massive limb, which eventually cracked under all the force. Finally, Mike stopped the vehicle. "Mike," Jono laughingly started, "Come take a look at this — there's no way they're getting these off now." Mike climbed down the side of the vehicle for a look as I clambered over three rows of seats to get a look. The limb had literally been warped and pressed onto the others. We were fully convinced that the elephants would not be able to get those off. Satisfied with our work we all sat back in the vehicle, watching the elephants once more before heading back to camp. Much to our disappointment, though I wasn't incredibly surprised, by the time we returned to Hidden Lagoon the next afternoon our contraption had been completely removed by the elephants, serving as a humble reminder of their vast strength compared to our own.

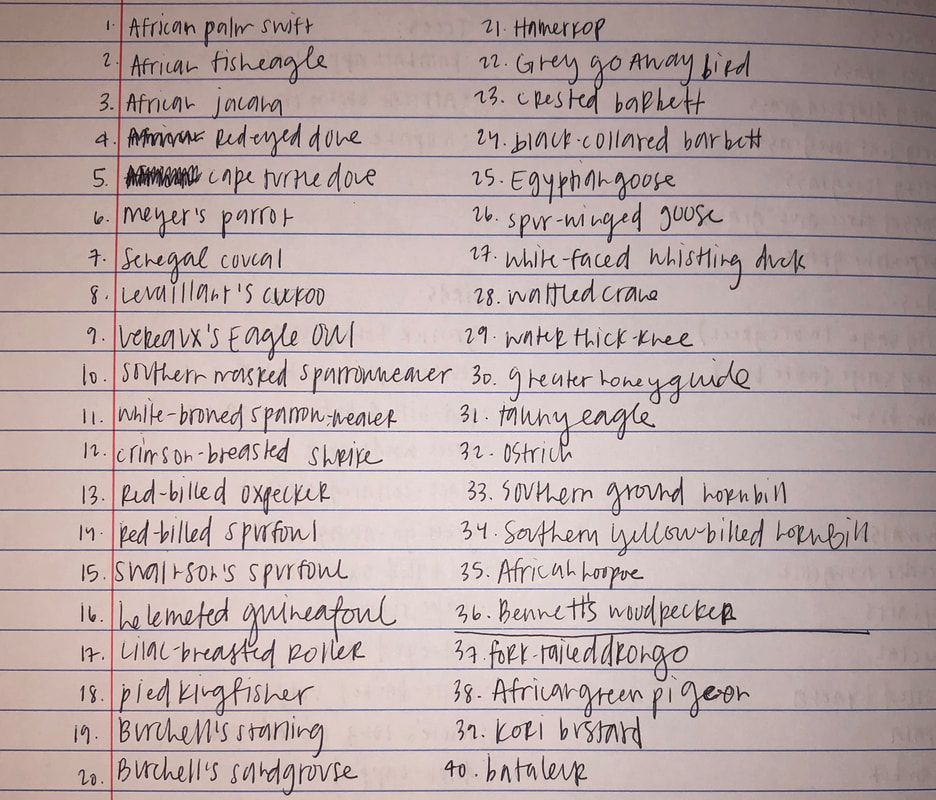

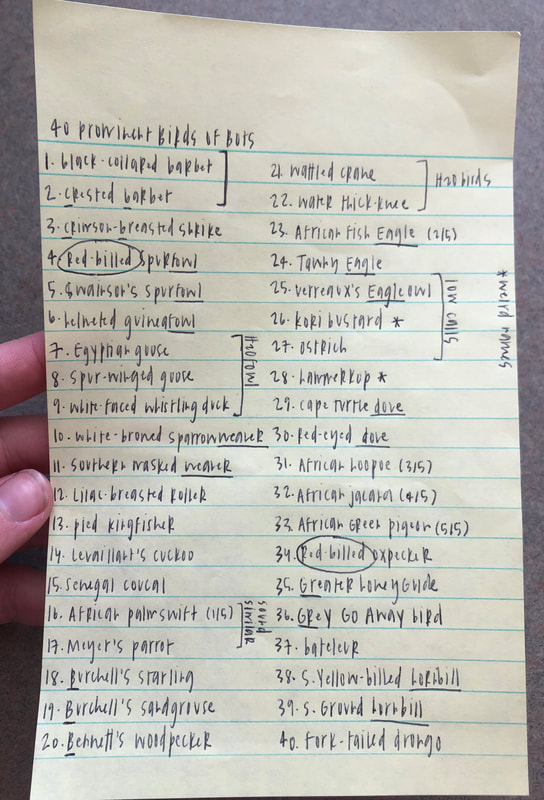

That afternoon serves as one of my favorite memories from my first trip to Botswana, and it is a treat to vicariously relive it on this World Elephant Day. Starting any new thing can be an intimidating task, and dipping one's toe into the world of bird watching is no different. With over 2,000 bird species in North America and nearly 18,000 bird species in the world, birding can definitely seem like an overwhelming hobby to start. I found myself in that camp nearly a year ago when I was in the middle of the Okavango Delta studying for an exam that included being able to recognize 40 different bird species both by sight and by sound. Prior to my preparation for the trip, I had heard of maybe three of the bird species that we had to recognize -- not very many at all. I spent the first week trying to figure out how the heck I was going to learn the names, appearances and calls of all these birds while simultaneously learning the material from fourteen other modules in a month's time. I considered using Quizlet but felt like it would take away from the whole unplugged, middle-of-the-bush vibe. After toying with some ideas, I finally landed on a method that was incredibly successful for me and my learning style. I'll be sharing it with you, as I've gone on to apply it even back home as a growing birder.

After I made my first list I immediately made another list, trying to recall the different patterns that I'd recognized. I remembered more birds but still had to call upon the aid of my master list. And then I did it again and again and again and again, literally filling pages and pages of my notebook with a repeating list of 40 prominent birds of Northern Botswana. As the days went on and I continued making lists, it became easier and easier to recall the birds. *Side note: I'm a HUGE proponent of writing things down instead of typing them — a quick Google search of 'writing vs typing memory' will result in numerous scholarly articles highlighting the benefits of handwriting when concerning memory.* Even upon returning to the States, I wrote the list over and over again on anything — napkins, Band-Aid wrappers, planner margins, notebooks, scrap paper, etc. — in order to remember the names of these birds (and I still do). So how do you apply this practically? Wherever you live, Google common birds in your region. For me, I Googled 'common birds of North Carolina' and developed a list of 40+ birds. Write the list down by hand (40 really isn't too scary of a number, I promise). Study it. Read it. See what birds you might already know and what birds you're completely unfamiliar with. Find patterns in your list. How many raptors/owls/wrens/water birds/etc. are there? Do any birds have a color in their name? Are there any birds with similar names? Ask questions. Find silly patterns that help the names stick and solidify in your mind. And then write the list down again. And again. And again. Do it once during breakfast, maybe again at lunch, take a brain break from your primary occupation to jot down the list again, think about the list on your way to/from work, etc. Anytime you feel like it, try to recall the list. The more often you do it, the quicker you'll get it down.

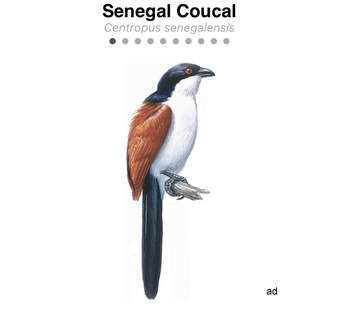

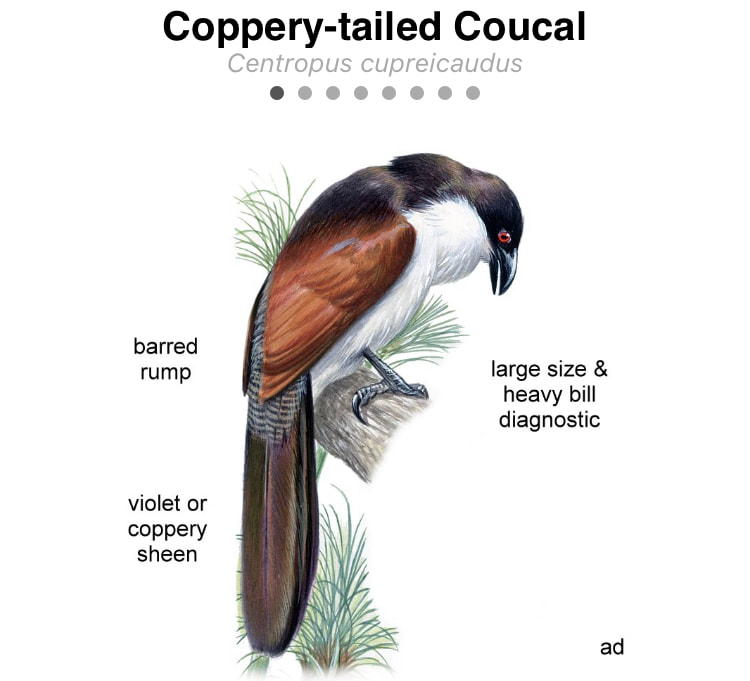

Once you start paying more attention to birds, the easier it becomes. You start to notice differences in body types even if you see two birds of a similar color. Take note of sexual dimorphism, that is, the differences in appearance between males and females of the same species, such as in color, shape, size, and structure, that are caused by the inheritance of one or the other sexual pattern in the genetic material. For example, male cardinals are characteristically a brilliant red whereas females are a light brown with only tinges of red. In other species, such as the Florida scrub jay, both male and female morphs appear the same. There can also be differences when it comes to juveniles and adult size and plumage but, again, the more you bird, the more you'll become familiar with these differences. Note that this step doesn’t necessarily have to come after you've FINALLY memorized your list of birds. You can begin associating names with pictures, as it may be helpful while you're trying to memorize your list. The biggest point of getting a memorized list going is just to help you not jump into birding blindly. Associate each one with its proper call. Ahh, now to bird calls. I'm not going to lie, this is the most difficult part of the learning process for me, especially if I'm trying to learn the calls on my own. I'm a huge proponent of letting others help you, particularly when it comes to identifying bird calls. Personally, I have a fear that if I'm studying calls on my own I'll incorrectly learn and identify a call, which would eventually result in me having to unlearn the incorrect call and relearn the proper one (that's part of the reason I started the Charlotte Nature Journal Club, so that people can meet and learn about different aspects of nature together). Anyways, back to bird calls. In Botswana I learned that there is a German word — eselsbrücke — that literally translates into "donkey bridge" and refers to any mnemonic device or phrase that is used to remember facts or information. A very common example in English is "PEMDAS" (Parentheses, Exponents, Multiply, Divide, Addition, Subtraction). Applying this to birding, you hear the call and try to see if it reminds you of anything. Taking a Senegal coucal, the donkey bridge used to remember its call is that it sounds like a happy little ghost laughing. It's silly, but I haven't forgotten the call of this bird. And in the States, a tufted titmouse, for example, sounds like it's whistle-ly saying "Peter-Peter" over and over again. Whatever donkey bridge works for you works for you, and you should share yours with other birders because it may help them remember that call too. If you're trying to learn these bird calls with a group of people, circle up and have a bird call brainstorming session: play different the bird calls and try to come up with a donkey bridge for each of them. Do be sure to note that some birds have multiple calls that you may want to learn too. The best way to get better at something is to start doing it, and this is how I got my foot in the door to birding. There are many more aspects to birding, such as learning behavior and identifying birds in the field, but both of those will come as you begin reading more about birds and spending more time with them. Allow yourself to be curious and ask questions. Do research. When you're in the field, take note of observations you see and questions that arise. Talk to others about what you saw, as they may be able to help further develop your understanding of what was observed. For both of these tasks, I find the Audubon Bird Guide App to be incredibly helpful. Each bird species is fairly thoroughly profiled in description, songs and calls, range, migration, conservation status, discussion, habitat, feeding behavior, diet, nesting and eggs. Intentionally reading through birds' profiles will help you learn more about them. You may also want to consider a field guide to the behavior of birds in your region. I don't have any recommendations for a specific guide, but a quick Google search will bring up a few options.

When you're trying to identify birds in the field, use GISS (General Impression of Shape and Size) as a general rule of thumb for noting different characteristics:

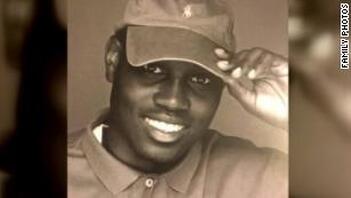

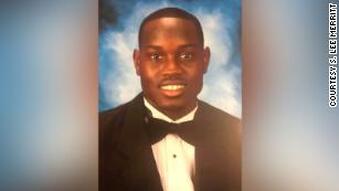

There's a feature on the Audubon Bird Guide App that walks you through each of these steps as you're trying to ID a bird, but I think they are important for you to know for yourself if you're away from your phone or if you have to make note of a bird very quickly. While it may seem like a lot to note, it definitely becomes more natural the more you do it. Just like any new thing, birding takes practice. Get out there and walk around. Use your list to start learning and identifying birds in your area. As you get out more, you'll find more birds that you haven't seen before or aren't familiar with. As you begin to identify those, they'll stick in your mind too! Learning is a very fluid process that looks different for a lot of people, so there is no "right way" to start birding. I just found this method to be incredibly successful for me in deterring the feeling of being overwhelmed. Now get out there and start birding! As always, let me know if this was helpful for you or if you have any recommendations of your own! Today my spirit has been heavy, harrowed with sorrow. Over the last couple weeks I have experienced the steadily increasing weight of the world’s burdens, but today it reached its tipping point. This morning as I distractedly completed my last final of the semester, I was overwhelmed with emotion and sadness for the family of Ahmaud Arbery, who, as I’m sure many of you know by now, was followed and fatally shot as he was jogging through a neighborhood in Brunswick, Georgia. I could hardly react, hardly process what happened (over two months ago, I might add). And yet, I experienced an irrepressible ache not only for the racial injustices and corrupt systems that plague the world but also for the injustices committed against the innocent on a daily basis. The part that saddens me the most is that WE are inflicting this pain upon each other and upon our planet. I look at nature, at animals, and I see innocence. I see creatures trying to survive. I see them dying at our hands, hit by our cars, driven out by our expansion, hunted for our pleasure. I see our planet being leeched of its resources. Our planet — and the animals that inhabit it — are desperately trying to adapt and survive to the changes we are so rapidly imposing upon them. It shatters my heart and brings me to tears that millions of animals are dying by our hands. But many people perceive nature and animals as cruel. They see a vulture scavenging a car-struck deer on the side of the road and don’t think for a second that it’s worth saving. They see a lioness kill a newborn zebra and a sympathy is evoked. But the seeming cruelty of nature — which is survival based — pales in comparison to the evil and cruelty that we are able to conjure in our hearts, lives and societies.

Humanity has become so comfortable in its own sin that when people see something as fundamental as survival in the wild they call it ‘cruel’ whilst simultaneously overlooking the far more horrid injustices we commit to our brothers and sisters. We have convinced ourselves that we are good enough on our own. When I look at humanity, I see our desperate need for a Savior. It’s obvious that we aren’t able to fix the problem ourselves or we would’ve figured out a way to do so by now. We have forgotten our humanness, our brokenness, our innately evil tendencies. We have forgotten how badly we need someone to save us. I called my mentor crying, asking him how he deals with the weight of all the evil in the world. And he reminded me that it serves as a reminder of our desperate need to be saved. It unmasks our humanity, showing us the reality of the human condition, and it makes room for Jesus to come in and heal our hearts, our lives and our societies if we let Him. The hope we get to cling to is named Jesus — He will come and rule the world one day with truth and justice. Until then, we get to cling to the promise that He will do so. I did a lot of wrestling today. A lot of contemplation with the Lord. A lot of allowing myself to feel everything. I felt physically heavy, a tangible weight pressing on my shoulders. I cried at the world’s brokenness. I cried at the fact that we live in a world in which people are more appalled at the seeming cruelty of nature than they are at mankind’s ability to hate and steal and murder. I cried at the fact that some people will never get to taste the assurance of the hope named Jesus. I cried to the Lord. Then I thanked the Lord for His promise of hope. I thanked the Lord that one day He will rule with truth and justice on the earth. I thanked the Lord that one day we and all creation will be free from the bondage we have made ourselves slaves to. I encourage whoever is reading this to feel everything you are feeling. Feel the anger, the brokenness, the sadness, the pain, the confusion and anything else. Cry. Lament. Talk to God. Allow yourself to be vulnerable with Him. Ask Him to bring up new things and comfort you in new ways. Allow Him to do so. Commit your hope to the coming of Jesus.

If you’ve never experienced Jesus in this way before, if you have any questions or if you need to just talk, please reach out to me. I’d love to chat with you. |

1 Thess. 2:2"...but with the help of our God we dared to tell His gospel in the face of strong opposition." Categories

All

Archives

April 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed